Posthuman Feminist Theory: Body Modification and Empowerment

Technology and the Body: Care, Empowerment and the Fluidity of Bodies, OII, Istanbul, Turkey, 21 January 2020

wissen.hypotheses.org︎︎︎

WHAT IS POSTHUMAN?

Although varied in use and meaning, post-human, refers to the idea of enhancing the body through technology to transcend bodily limitations in order to actualize a better self and a sense of empowerment. The body in post-humanist thought is malleable, meaning, it is used as the foundation to give shape to for self-actualization purposes. In that sense, body modification practices constitute a key area to understand and contribute to posthuman theory.

Post-humanism is a stance against the universalist notion of ‘man’ and human exceptionalism, and thus humanism. Post-humanist thought is a critique towards the notion of (male, white, European) human in humanist tradition, and rejects the privileged, western, affluent transhumanist subject. Post-humanism challenges the more anthropocentric tendencies of both schools of thought and attempts to attain more-than-human understandings and imagines human subjects having given up of their privileged positions. It embraces natureculture continuum, humanimal subjectivities. Rosi Braidotti, in her article titled “Posthuman Feminist Theory”, explains the roots of posthuman feminist thought as feminist anti-humanism and anti-anthropocentrism. Feminist anti-humanism rejects the universal ideal of man of humanist school, whereas anti-anthropocentrism criticizes species hierarchy and attempts ecological justice.

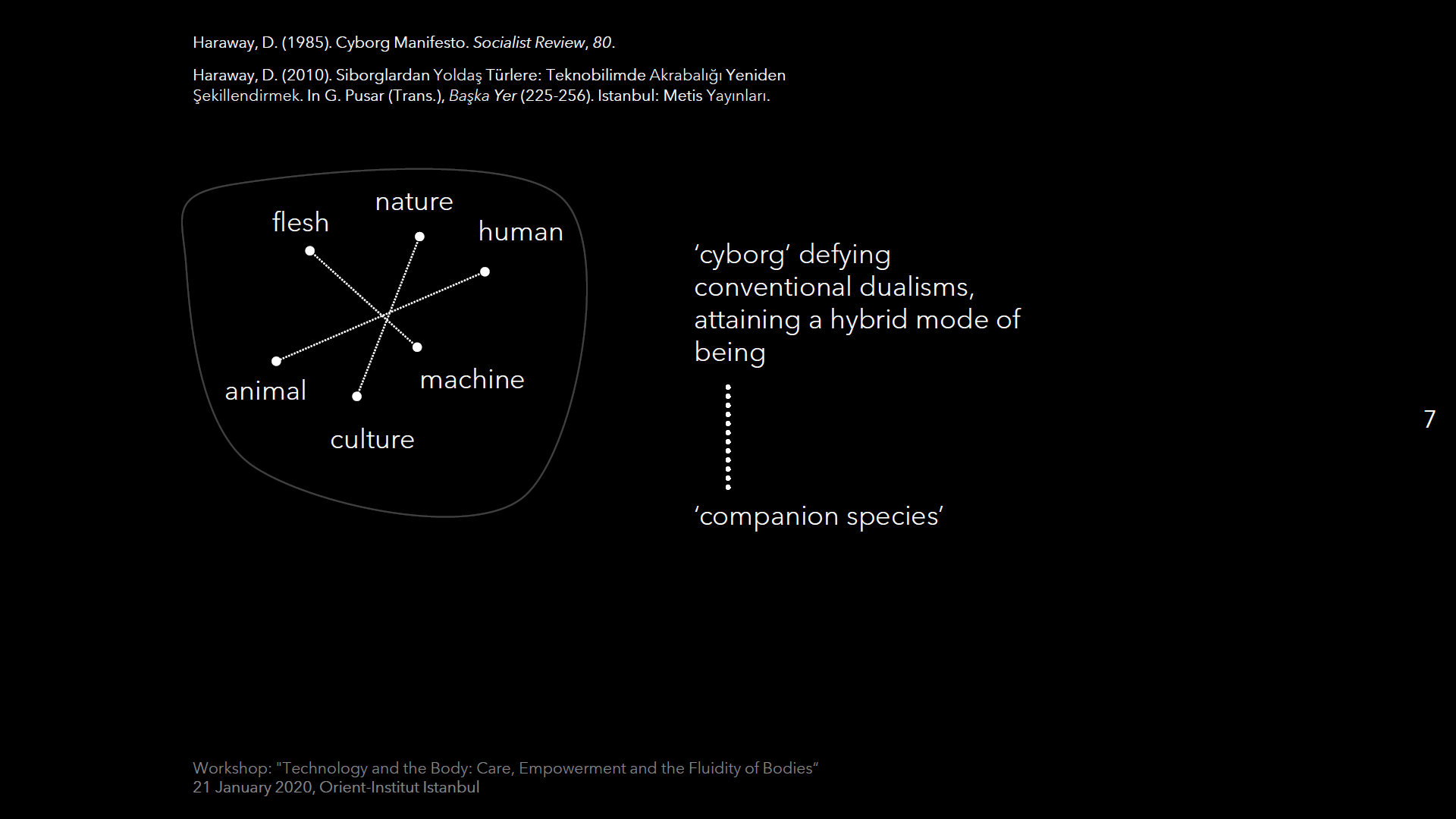

Donna Haraway, one of the key scholars in post humanist thought as suggested by Rosi Braidotti,1 discusses the concept of cyborg in her widely acclaimed “Cyborg Manifesto” as a mode of being that defies the dualisms of nature and culture, human and animal, flesh and machine2 in a very, to cite Braidotti, “non-nostalgic” way.3 Later, in her “Cyborgs to Companion Species: Reconfiguring Kinship in Technoscience”, Haraway expands on her previous dissolution of dichotomies and argues that anything can be a companion for nothing constructs itself on its own.4 Therefore, post humanist thought suggests a conceptualization of human embedded in a relational web of human and non-human actors, such as medical technologies, co-constructing and depending on one another, rather than being isolated.

Slides: Burak Taşdizen

Sullivan, in her article “Transsomatechnics and the Matter of ‘Genital Modifications’”, provides a general overview and a critique of differing accounts to the study of body modifications, namely, isolationist approach, analogical approach, and categorical approach.5 Sullivan argues that these approaches are problematic for they either consider body modification practices in isolation from one another, or through problematic analogies between different practices, lacking an intercorporeality approach.

Instead, similar to Haraway’s account of cyborg and companion species, an intercorporeal approach is called for. In a similar vein, Garner argues that the concept of “becoming” is helpful to think beyond the dichotomies such as nature and culture, and to challenge, say, the accusation that trans bodies are unnatural or constructed (ibid., p. 30).6

To conclude, posthuman is a new ontology for the human, centering around the human body, which becomes a malleable matter for ongoing work on enhancement and dissolves conventional dichotomies and embraces ambiguity, in-between-ness, and fluidity. The body in posthuman thought is not passive, and the co-construction of the posthuman body is an ongoing negotiation between the body and the medical technology, the doctor and the patient. The posthuman body is embedded in a web of interrelated actants, human or non-human, and operates within power structures that are both restrictive and productive.7

LOOKING BEYOND THE WEST

Body modification such as cosmetic surgeries emerges as a more accessible phenomenon compared to past decades, democratizing the opportunity for body modification and self-actualization.8 Although not exclusive to one gender, cosmetic surgeries discussed in the literature illustrate a gendered practice-Women constitute the wider clientele9 going through body modification procedures after pregnancy or menopause to reshape the body parts including (but not limited to) waist, breast, vagina, bosom, nose, eyelid, etc. in elective surgeries called ‘Mommy Makeover’.

Although the undesired body parts vary according to individual patient/gender and the geography under scrutiny, statistics and observations disclose an increasing demand for these body modification procedures. According to an article on Turkish newspaper Hürriyet, %80 of patients undergoing cosmetic surgery in Turkey are women leading a corporate lifestyle.10 According to a statistic in the US, 400.000 women with children went through cosmetic surgeries in 2007.11

Gazagnadou discusses how it is common to witness women, and sometimes men, in everyday Iran with surgical dressings on the nose.12 Edmonds in his article "Learning to Love Yourself: Esthetics, Health, Therapeutics in Brazilian Plastic Surgery" argues that critiques of enhancement technologies have focused on the West, probably with the assumption that these are problems of the consumers in Western societies.13 His case focusing on Brazilian plástica shows otherwise. This also holds potentials for further research on body modification and empowerment, in geographies such as Turkey and Iran, with an increasing industry of cosmetic surgery and sex-change operations.14

BODY MODIFICATION

As discussed in the literature, not all body modification practices are interpreted within the framework of empowerment. On the contrary, some of these medical interventions are discussed to conform to and reinforce normative ideals of how a body should look, operate, etc.

Walker illustrates a sharp dichotomy between non-mainstream body modification practices (tattooing, piercing, etc.) and cosmetic surgery, regarding the former as a radical practice, whereas discussing cosmetic surgery as first surrendering to masculine medical practice, and then to patriarchal ideals of beauty in general.15 In her comparison of cosmetic surgeries undertaken by women and ORLAN’s performances utilizing body modifications,16 Davis undermines and depoliticizes women’s body modification practices.17 From a more radical perspective, Jeffreys argues that women’s cosmetic procedures are similar to female infanticide, that is, the elective killing of newborn female babies, for they constitute a ritualized violence against women.18 These discussions of body modification practices in the case of women patients, undermine women’s agency, producing a stereotypical, victimizing image. Whether this is true, needs to be studied through firsthand experiences of women undergoing such procedures.

Türker’s discussion of intersex activism in the case of intersex children in Turkey is a telling example to how intersex children’s gender-ambiguous bodies are first problematized by medical practice and then molded into gender dichotomy in early ages, silencing the agency of intersex individuals.19

In a similar vein, postnatal female bodies, too, are problematized requiring and justifying the need for medical intervention on women’s bodies, which, according to some scholars, is subscription to patriarchal ideals of beauty, and a particular type of femininity. What I find compelling here is the problematization of certain bodies such as the postnatal female body or the intersex infant body by medical practice calling for an intervention which will then “correct” them, “fix” them in their supposed-to-be positions. However, the totalizing and almost victimizing discourse surrounding body modification practices such as cosmetic surgery is something to be critical of, for studies do point to narratives of self-actualization.

If we go back to the definition of the posthuman, we know that bodies are neither static nor isolated but are embedded in a web of relations constituted by human and non-human actors, constantly co-constructing one another.

Nikki Sullivan, in her article “Transmogrification: (Un)Becoming Other(s)”, develops an encompassing approach to body modification practices. She argues that all cosmetic procedures, albeit diverse, transform bodily being in varying ways and to varying degrees, and that they are trans practices.20 In that sense, a study focusing on the (re)construction of postpartum female vagina, and the construction of trans female vagina becomes a departure point to understand the construction of different femininities through medical technology. Another potential area of research would be the disciplining of male facial and bodily hair, which could provide us insights into the construction of, say, aging masculinities.

Moving away from the notions of cosmetic surgery operating within patriarchal normative ideals of beauty, and transsexuality as a gender dysphoria problem, Sullivan’s account calls to investigate the similarities (and differences) between these procedures through the lens of empowerment and the right to difference.21 Braidotti argues that science and technology studies focusing on the posthuman condition, do not interrogate the posthuman subjectivity and its political implications, favoring a segregated approach. Braidotti calls for “a re-integrated posthuman theory that includes both scientific and technological complexity and its implications for political subjectivity, political economy and forms of governance.”22 Rejecting the totalizing, victimizing accounts on cosmetic surgeries and reclaiming the agency of the patient and the self-will (Eigensinn) of the body, I argue that the posthuman subject is both the product and the producer of their own body and their own being attaining towards self-actualization and empowerment. The ever-increasing cosmetic surgery industry in both Turkey and Iran, with their differing socio-cultural formations and forms of governance, presents itself as a potential research area to understand how the posthuman subject is co-constructed in the Non-western context.

REFERENCES

- Braidotti, R. (2016). Posthuman feminist theory. Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory, 673.

- Haraway, D. (1985). Manifesto for cyborgs: science, technology, and socialist feminism in the 1980s. Socialist Review, no. 80 (1985): 65–108.

- Braidotti, R. (2016). Posthuman feminist theory. Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory, 673.

- Haraway, D. (2010). Siborglardan Yoldaş Türlere: Teknobilimde Akrabalığı Yeniden Şekillendirmek. In G. Pusar (Trans.), Başka Yer (225-256). Istanbul: Metis Yayınları.

- Sullivan, N. (2009). Transsomatechnics and the Matter of ‘Genital Modification’. Australian Feminist Studies, 24(60), 275-286.

- Garner, T. (2014). Becoming. Transgender Studies Quarterly, 1(1-2), 30-32.

- Braidotti, R. (2016). Posthuman feminist theory. Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory, 673.

- Abate, M. A. (2010). “Plastic makes perfect”: My beautiful mommy, cosmetic surgery, and the medicalization of motherhood. Women's Studies, 39(7), 715-746; Edmonds, A. (2009). Learning to love yourself: esthetics, health, and therapeutics in Brazilian plastic surgery. Ethnos, 74(4), 465-489; Gazagnadou, D. (2006). Diffusion of Cultural Models, Body Transformations and Technology in Iran: Iranian Women and Cosmetic Nose Surgery. Anthropology of the Middle East, 1(1), 106-111.

- Davis, K. (1997). ‘My Body is My Art’: Cosmetic Surgery as a Feminist Utopia? European Journal of Women’s Studies, 4(1), 23-37; cited in Abate, M. A. (2010). “Plastic makes perfect”: My beautiful mommy, cosmetic surgery, and the medicalization of motherhood. Women's Studies, 39(7), 715-746.

- Yenal, Merve. “Benim Güzel Müdürüm” Hürriyet, 5 June 2004. Retrieved from https://www.hurriyet.com.tr/kelebek/benim-guzel-mudurum-231334. 01.10.2020.

- Abate, M. A. (2010). “Plastic makes perfect”: My beautiful mommy, cosmetic surgery, and the medicalization of motherhood. Women's Studies, 39(7), 715-746.

- Gazagnadou, D. (2006). Diffusion of Cultural Models, Body Transformations and Technology in Iran: Iranian Women and Cosmetic Nose Surgery. Anthropology of the Middle East, 1(1), 106-111.

- Edmonds, A. (2009). Learning to love yourself: esthetics, health, and therapeutics in Brazilian plastic surgery. Ethnos, 74(4), 467.

- Liebelt, C. (2016). Beautifying Istanbul: on neo-liberal selves and aesthetic body modification as a form of Surveillance Medicine. Paper presented on on 21st July 2016, during the 14th EASA Biennial Conference; Gazagnadou, D. (2006). Diffusion of Cultural Models, Body Transformations and Technology in Iran: Iranian Women and Cosmetic Nose Surgery. Anthropology of the Middle East, 1(1), 106-111.

- Walker, L. (1998). Embodying Desire: Piercing and the Fashioning of ‘Neo butch-femme’ Identities”. In Munt, S. (Ed.), Butch/Femme:

Inside Lesbian Gender. London and San Francisco: RE/Search Publications; cited in Sullivan, N. (2013). Transmogrification: (Un)becoming other(s). In The transgender studies reader (pp. 568-580). Routledge. - ORLAN (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.artnet.com/artists/orlan/.

- Davis, K. (1997). ‘My Body is My Art’: Cosmetic Surgery as a Feminist Utopia? European Journal of Women’s Studies, 4(1), 23-37.

- Jeffreys, S. (2014). Beauty and misogyny: Harmful cultural practices in the West. Routledge.

- Türker, H. (2019). İnterseks çocuklara yönelik tıbbi müdahale sorunu bağlamında toplumsal cinsiyet ve beden. Kaos GL.

- Sullivan, N. (2013). Transmogrification: (Un)becoming other(s). In The transgender studies reader (pp. 568-580). Routledge.

- Ibid.

maxweberstiftung.de︎︎︎

oiist.org︎︎︎

hairyless.hypotheses.org︎︎︎

instagram︎︎︎

wissen.hypotheses.org︎︎︎

This presentation was produced as a part of Hair:y_less Masculinities. A Cartography, a subproject within IRSSC. IRSSC was led by Orient-Institut Istanbul within the scope of Max Weber Foundation’s international research project Knowledge Unbound (Wissen Entgrenzen), which was funded by German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).